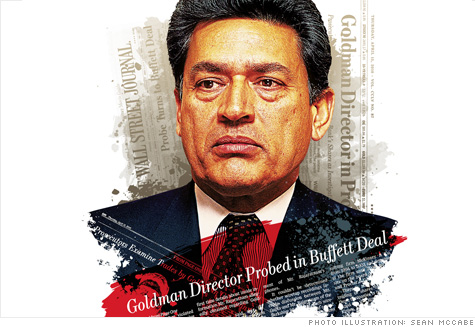

FORTUNE -- This is not the way the Rajat Gupta story is supposed to end. It's supposed to go out on a high note, like the previous chapters. He is an Indian nationalist's son who made it to Harvard Business School. He's the only non-Westerner to have served as managing director of storied management consulting firm McKinsey & Co., adviser to CEOs the world over. The ultimate behind-the-scenes business operator, Gupta over the years has whispered in the ear of everyone from Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs to Bill George of Medtronic to A.G. Lafley of Procter & Gamble. More recently he's become a global philanthropist who rubs shoulders with Bono, Bill Clinton, and Bill Gates, tackling problems like malaria in Africa and AIDS in India.

And yet today, at 61 years of age -- a time when he should be taking victory laps -- his reputation hangs in the balance because of news reports that have linked him to the biggest insider-trading scandal in hedge fund history.

In a front-page article on April 15, the Wall Street Journal reported that the government was investigating whether Gupta had shared confidential information with his onetime friend and business partner Raj Rajaratnam, the hedge fund heavyweight whose $3 billion Galleon fund disintegrated in October 2009 after authorities announced sweeping charges of illegal trading. The ongoing Galleon investigation includes an examination of trading in shares of Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500). The government's filings don't name names, but in a second front-page story the Journal, citing an unnamed source, reported that Gupta -- a member of the Goldman board since late 2006 -- had tipped off Rajaratnam about Warren Buffett's confidence-boosting $5 billion investment in the teetering investment bank in September 2008, during the depths of the market turmoil. Gupta left the Goldman board in May when his term expired rather than stand for reelection. To date, no criminal charges have been filed against Gupta.

Gupta's defenders say that any suggestion of impropriety is absurd for a man whose exemplary reputation has been built on the twin pillars of integrity and discretion. But Gupta's close association with Rajaratnam invites scrutiny. Government filings for a private equity firm that the two co-founded listed one of Gupta's homes as Rajaratnam's contact address as recently as 2008. They ran in the same social circles in New York, and, according to the Journal, Gupta was a frequent visitor at the Galleon offices. Other connections also raise suspicion. In January, Gupta's former protégé at McKinsey, Anil Kumar, pleaded guilty to providing Rajaratnam with confidential information. Kumar admitted taking a total of $2.6 million in exchange for revealing secrets about McKinsey clients, including chipmaker AMD

It bears repeating: The government, which has hardly been reluctant to sling criminal charges in the Galleon case -- 21 people have been charged to date, and 12 have pleaded guilty to various charges -- has yet to accuse Gupta of anything. But he remains in limbo nonetheless, counseled to keep quiet by advisers while the legal process plods forward.

Through a spokesperson, Gupta declined repeated requests to speak with Fortune for this article. But his lawyer offers a defiant statement of his client's innocence. "Rajat Gupta's record of ethical conduct and integrity in his professional as well as personal life is beyond reproach," says attorney Gary Naftalis. "He also has served with distinction and selflessness many philanthropic and civic causes around the world, including both the United States and India. Rajat has not violated any laws or regulations, nor has he done anything improper."

Nevertheless, Gupta's limbo will probably persist at least until Rajaratnam goes to trial in January. (Rajaratnam has pleaded not guilty to all charges.) The outcome of a hearing scheduled for early October in which Rajaratnam's lawyers will challenge the admissibility of thousands of wiretapped conversations -- including, possibly, tapes of Gupta and Rajaratnam -- could have a significant bearing on the strength of the government's case. If evidence ultimately emerges that shows that Gupta provided Rajaratnam with confidential information, his exemplary reputation will be obliterated and his board positions at companies like P&G (PG, Fortune 500) will no doubt vanish.

For now we are left with questions. Rajat Gupta spent his entire career at McKinsey, getting access to the privileged information of the companies McKinsey consulted. His post- McKinsey career has been built on utilizing the connections that he made during that time. Did he lose sight of the line between the two?

The Gupta era at The Firm

Rajat Kumar Gupta was born Dec. 2, 1948, in Calcutta. The second of four children, he and his family moved to Delhi in 1953. His father, a journalist fighting for Indian independence, served time in prison under the British on more than one occasion. His mother was the principal of a Montessori school. Both parents had died by the time Gupta was 19 years old.

After studying mechanical engineering at the famed Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, he applied to and was accepted at Harvard Business School, graduating in 1973. Like many HBS graduates, he interviewed for a job at McKinsey -- but was initially rejected. But the resourceful Gupta prevailed on a Harvard professor with McKinsey connections to put in a good word. After a full day of further interviews, Gupta was invited to join McKinsey's New York office as an associate. He spent the next 34 years at the company that calls itself The Firm, becoming an American citizen along the way. In 1994, the firm's 148 senior partners voted him worldwide managing director, a post he held for three three-year terms, the maximum allowed.

As the head of McKinsey and the senior counselor to its top clients, Gupta had a hand in some of the biggest corporate decisions of his time, including Procter & Gamble's 2005 acquisition of Gillette, a deal he helped conceptualize with P&G's then-chairman and CEO, A.G. Lafley. "Rajat starts from purpose and values and ends up at strategies and principles," says Lafley. "He also brings an analytical and objective approach to the question at hand. I think of him like Thomas Aquinas. He wasn't just asking what we should do. He was helping us figure out the right thing to do."

Every leader has his detractors, however, and Gupta did not lack for them. McKinsey grew rapidly during his tenure -- there were 3,300 consultants when he took over as managing director, and 7,700 when he stepped down -- and to many McKinsey traditionalists, it was too much, too fast. The firm opened 23 offices in 20 countries during the Gupta era.

For decades a restrained approach to growth had allowed McKinsey to nurture its culture of elitism and to perpetuate its image of working only for the executive in the corner office. But when you're fielding nearly 8,000 consultants and bringing in nearly $4 billion annually, it's harder to make that claim. "McKinsey used to interview only the Baker Scholars from Harvard Business School," laments one disenchanted alumnus. "By the time Rajat was done, the firm interviewed just about anybody who wanted to be interviewed, and you had about a one-in-three chance of getting an offer. That kind of changes the sense of an elite status."

Under Gupta, McKinsey also became more aggressive in its pursuit of big paydays. His predecessors had consistently refused to accept equity stakes in client companies in lieu of cash as payment for McKinsey's services. Forgoing potential IPO riches gave them the high ground when it came to their advice: McKinsey consultants didn't emphasize short-term stock price performance over long-term wisdom. During Gupta's tenure, that policy was jettisoned as McKinsey sought dotcom lucre along with everyone else.

McKinsey's reputation for insight also took a hit when the company got caught up in the euphoric -- and ultimately fraudulent -- growth of Enron, which was not only a major client but also had a former McKinsey man, Jeff Skilling, as CEO. Asked whether McKinsey strayed from its values during the Gupta era, Ian Davis, who succeeded Gupta as managing director in 2003, says, "The pressure on the firm from the outside was considerable, and some of our values were under stress. But this was not about Rajat alone. It is worth emphasizing that you don't get elected three times unless you are doing well in the eyes of your colleagues."

One fact that's hard to argue with is that during Gupta's tenure he and his partners became exceedingly rich. As a private partnership, McKinsey doesn't divulge its finances, but estimates of Gupta's take as managing partner run to more than $5 million annually. After becoming managing director, he and his family moved into an $8 million mansion a stone's throw from Long Island Sound in Westport, Conn., that was once owned by the J.C. Penney (JCP, Fortune 500) clan. Gupta's winter getaway is a sprawling $4 million oceanfront house on Palm Island, a private resort on Florida's gulf coast. By one estimate, he is now worth $100 million or more.

By the time Gupta retired from McKinsey in 2007, he was already well on his way to a second career as a global citizen and bigtime philanthropist. In 2001, he helped raise $1 billion in relief funds in the wake of the Gujarat earthquake in India. In the process he co-founded the American India Foundation with Bill Clinton. Gupta subsequently co-founded the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. He has taken on roles with the United Nations and joined the board of the World Economic Forum.

His long career as a well-connected corporate consigliere made Gupta highly coveted as a director. Between 2006 and 2009, Gupta picked up seats on the boards of five public companies -- American Airlines parent AMR (AMR, Fortune 500), global outsourcer Genpact (G) (of which he is also chairman), Goldman Sachs, audio equipment giant Harman International (HAR), and Procter & Gamble (see table). He also joined the supervisory board of Russia's Sberbank and the board of the Qatar Financial Centre. Altogether, those positions paid him more than $3.2 million in 2009.

Gupta has drawn criticism for his hefty board income. He left his position with Sberbank in June. But in 2008, he was paid $525,000 -- more than he made for his Goldman board seat -- to sit on the board of the bank, the largest in Russia and Eastern Europe by assets, while the next-highest-paid director earned only $110,000. The question of whether he could actually be "independent" while being paid $525,000 was a serious enough one that RiskMetrics, the corporate-governance watchdog based in Washington, D.C., advised minority shareholders to vote against his nomination in 2009. He was reelected anyway.

When Gupta joined the board of Goldman in November 2006, he seemed a perfect fit -- the former top executive of one secretive, elite firm joining another. Less than two years later Gupta reportedly told Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein that he wanted to step down -- he had spread himself too thin -- only to be persuaded to stick around to avoid the public relations fallout of a director quitting in the midst of the financial crisis. The recent publicity has turned out to be much worse. But fellow Goldman director Bill George, the former Medtronic (MDT, Fortune 500) CEO, says the board will miss Gupta's presence. "On boards of directors, you find out who really matters during times of crises," says George. "And in the fall of 2008, Rajat was an extraordinarily valuable member of the board. I was very disappointed to learn of his decision to step down. And as for the issues with Mr. Rajaratnam, no one [on the board] knows anything. No one has been contacted."

Fast friends and business partners

Gupta got to know Rajaratnam in the mid-2000s when he contacted the Sri Lankan-born hedge fund manager to thank him for making a substantial donation to the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad. Gupta co-founded the school in the late 1990s and remains chairman. The two South Asian-born businessmen had nearly crossed paths before, notably in the late 1990s when they both invested in venture capital firm TeleSoft Partners. (Gupta remains an adviser to the firm; Rajaratnam is no longer an investor.) But after Rajaratnam's donation, they became fast friends.

Before long, they were in business together. In 2006, Gupta and Rajaratnam joined private equity veteran Parag Saxena and Mark Schwartz, a former Goldman Sachs executive, to found Taj Capital, an investment firm focused on South Asia, with plans to offer both private equity and hedge fund investment opportunities. The hedge fund portion never came to fruition, so Rajaratnam ultimately had no role in the operations of what came to be known as New Silk Route. (He remains an investor, however.) Schwartz ultimately dropped out. Gupta and Saxena went on to raise $1.4 billion through 2007 and 2008, of which $700 million has been invested. While they have had no "exits" for any of their investments, the performance of their portfolio holdings is tracking well, according to Saxena. There is no reason to believe that Gupta's and Rajaratnam's dealings in New Silk Route are under investigation.

Did his investment with Rajaratnam compromise Gupta? People who know him say the former consultant has shown a tendency to blur the lines between his professional and personal relationships over the course of his career. Consider Anil Kumar. There is no shortage of McKinsey sources willing to claim that Kumar's success at the firm depended more on his friendship with Gupta than on his ability as a consultant. Then there's the fact that SEC filings for New Silk Route's Asian private equity fund list Gupta's home address in Westport as Rajaratnam's mailing address. Is that evidence of anything untoward? No. But it is perhaps a telling example of the fact that the boundaries in Gupta's extensive network are not always clearly delineated. Did they become even blurrier with success, comfort, and age?

When pressed as to whether it's possible that Gupta might have spilled Goldman's secrets to Rajaratnam, a handful of Gupta's supporters suggest that if he did share any confidential information, it must have been "unknowingly." But the former McKinsey über-consultant is far too savvy for that explanation to be plausible. If you're looking for a best-case scenario, it's probably that Gupta is guilty of nothing more than poor judgment in his choice of friends.

No matter how things turn out, that circle of friends no longer includes Raj Rajaratnam. While Gupta hasn't spoken publicly since March, sources close to him say that he and Rajaratnam had a personal and professional falling-out before September 2008, when Buffett made his investment in Goldman. Gupta wasn't even on speaking terms, in other words, with the man to whom he is supposed to have been feeding information. If that sounds like spin, it very well could be. But it also might have the virtue of being true. Since neither Gupta nor Rajaratnam is talking, it's impossible to know for sure.

So what's next? As more time passes, it seems less likely that Gupta will ever be charged. (Meanwhile, both the SEC and the Department of Justice are looking into "leaks" in the case.) Gupta's bigger problem may be not that he is actually charged with a crime, but that it's easy to believe he might have committed one. The government does believe that Rajaratnam traded in shares of Goldman based on inside information. If you were making a list of who might have given him that information, Gupta's name would certainly be on it. Speculation won't cease until the government makes its case against Rajaratnam.

Meanwhile, Parag Saxena is forced to see the names of his two partners at New Silk Route in the news for all the wrong reasons. "Regarding Rajaratnam, I cannot explain what I read in the papers," he says. "So I am going to wait and see what happens, along with everyone else. As for Rajat, it is absolutely out of the question that he would do what the papers have suggested he has done."

Pressing on through a crisis

Despite the uncertainty, Gupta is showing no signs of backing away from his public life. He still holds board seats at four public companies. The International Chamber of Commerce made him chairman in June. And as far as successful Indians are concerned, he's still in the club. "I find him of exceptionally good character," says multibillionaire Indian industrialist Adi Godrej. "He is extremely devoted to helping India's development and progress, things he doesn't have to spend his time and energy on."

But his ability to stay effective in that mission may hinge on what happens in the Rajaratnam trial. In a 2008 speech to the Leaders in Dubai Business Forum, Gupta offered a wise observation to his audience. "There's only one thing that's predictable about crises," he said. "Sooner or later, almost every organization will endure one." Gupta the global citizen has so many commitments -- private, public, for-profit, and philanthropic -- that he might as well be called an organization unto himself. Now he has his own crisis to endure.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar